Once Upon a Dining Table

The kitchen or dining room table is at the heart of the modern home. This is where we meet to enjoy a meal, good company, and to share the events of the day. It is an essential piece of furniture in our daily lives, and has been since the dawn of time. Well … not quite.

Who hasn’t imagined that they were Julius or his sweet Cleopatra, comfortably reclining—enjoying dish after dish of a lavish dinner—and remaining that way until fully satisfied? In fact, the dining table did not exist in Greek and Roman times; it became part of our ancestors’ daily lives somewhat later.

Among the Gauls in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, there were two ways to eat a meal depending on one’s social status. The rich would fill their bellies, reclining to imitate Roman chic, but they were also seated at times. The peasants ate on the ground, on animal pelts.

From the earth to the table

The glory days of the table as we now know it, began in the Middle Ages. However … before setting the table, you literally had to set up a table! This was because no room was dedicated to meals in castles and manor houses. The nobles would eat in large rooms with other guests, in their own bedrooms or in the garden. The less wealthy lived in humble one-room homes, where they went about their daily chores. This way of life would have made the fixed table of today quite cumbersome.

Setting the table is a modern expression, but originally, setting the table meant that this type of furniture was assembled with simple planks placed on trestles. The table had to be set up and then put away at the end of the meal.

It was around this time that, when seated at the table, guests would clink their glasses together—which is still done today—saying “chin-chin,” an expression originating from China meaning: “please”… Except that this practice, brought down from the Middle Ages, wasn’t meant to be polite, but was more of a fervent hope that they would survive the banquet!

At the time, many people died from poisoning at the hands of their table mates. Knocking glasses together caused liquid to flow from one vessel to the other, mixing the contents among the guests. And as a sign of trust, diners were to look into each other’s eyes when taking the first sip, another custom of yesteryear passed on to modern times. These table rituals were intended to reassure guests that they would still be alive after their drink!

A sedentary lifestyle gave rise to the fixed dining table as we know it. But the custom of setting up a table for each meal continued in humble abodes until the 18th century.

Meanwhile, across the globe

While people in Europe were struggling to set up and take down tables, the Japanese had found an ingenious way to combine fun with function with the kotatsu.

A central coal-burning hearth, heating their thin-walled homes, was covered with a platform, then a futon to conserve heat. This “table” was not only used to warm guests’ feet during meals, but also for food preparation and other activities.

It was a brilliant idea that has endured—nowadays electric kotatsus can be found in Japan. Many Japanese families still eat on the floor, gently warmed by their table and well wrapped under a thin futon.

The sun and his table

The table, as we now know it, first made an appearance in the 16th century, thanks in part to Louis XIV, an inspirational king who loved his food, who decided to decorate it and make it more prominent.

The Sun King, as he was called, considered French cuisine to be a way for him to shine—a way to demonstrate his power. With Louis, out went the planks and trestles, and in came a solid table—a real piece of furniture. Also, with the gilding and ostentation prevalent at the time, it was decorated from end to end with gold and silver tableware. The king was seated with his family at 10 p.m. for a big public meal, known as the Grand Couvert, a symbol of his power in the day-to-day.

Like the Gauls—who copied Roman and Greek habits to assert their status—nobles, followed by commoners, embraced the fixed table to show off their social and financial success.

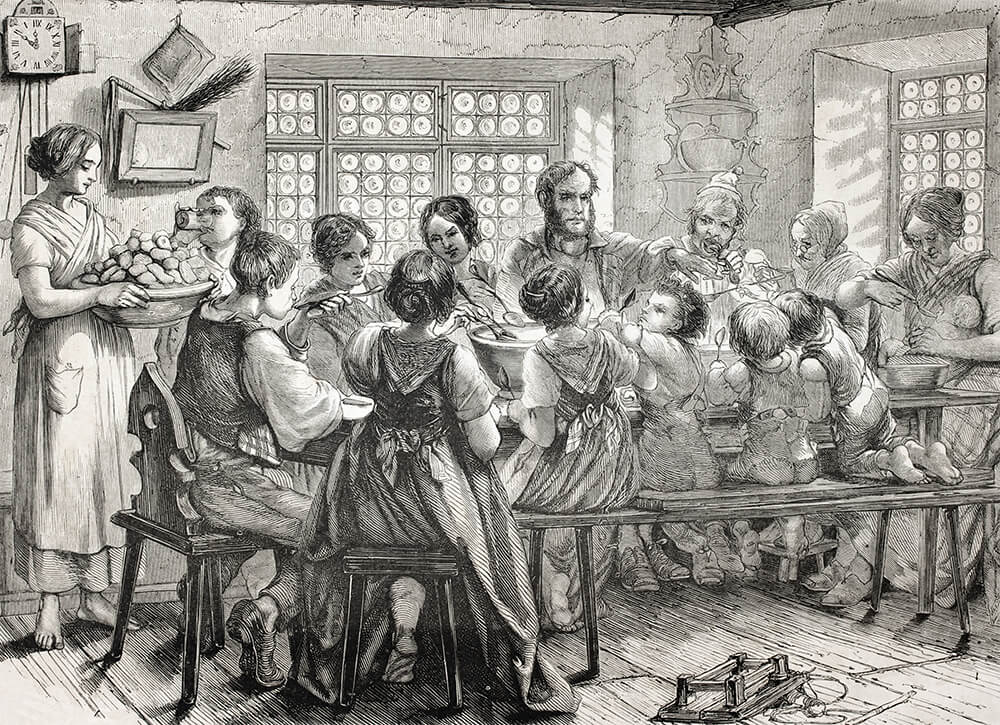

A table could not be a permanent fixture in the center of one-room homes, but from the 18th to the 19th century, dining rooms democratized and started to appear in middle-class homes. So now it was possible to get a fixed and more prestigious table, and to host with panache and etiquette, as it should be in “upper-class” family homes.

Table legs: out of sight, out of mind

Although austerity today has a more financial than social connotation, the Victorian-era table faced the judgment of Puritan times, when all forms resembling female curves were deemed scandalous, and that included table legs. For this reason, “legs” were considered inappropriate and unseemly and were hidden or covered to prevent fertile imaginations from running amok at the table.

This explains why the Chippendale style, comprised of hand-carved dining tables with sculpted and curved legs, gave way in North America to simpler tables, often influenced by the Shaker style. But the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the middle class heralded the return of more ornate dining tables—once again, to show off prosperity.

Today, the dining table is not only functional, it is also beautiful. In fact, the market now offers a wide range of tables that meet several needs—different extension systems to accommodate more guests, children doing homework, or those in a work-from-home setting—and different table sizes, making it possible to customize it to our personal living spaces.

Tables today brilliantly meet the expectations of the modern consumer, with classic or modern styles to match traditional or contemporary decors.